Engine Core

Engine Loop

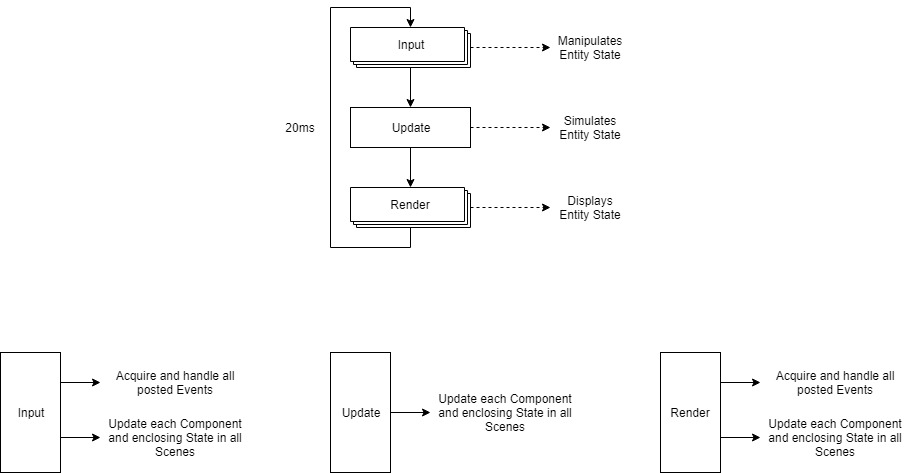

At its most basic, the engine loop can be split up into three simple phases: handling input, updating, and rendering. Although there are a couple different designs of this loop, ranging in complexity, I decided to use the fixed timestep loop, which has become the de facto standard for modern engines. In this loop, the game simulation is updated at a fixed rate (20ms in our case) while input and rendering are free to run as fast as they can. Each of these three phases play a very important role in how the state of the simulation progresses over time. The input phase is responsible for manipulating the state of each entity in the simulation, the update phase is responsible for simulating the state of each entity and then storing these results, and the render phase is responsible for displaying entity state.

All update-driven parts of the engine (in other words, the parts of the engine that respond stuff that happens while the program is running - be it a change in time, a button press, or resized window) can be divided into two groups: entities and modules. Every object in a game world is an entity, and is comprised of a collection of different components. Modules, on the other hand, are the systems that operate in the background to support their respective components. Now, what exactly drives the updates differs between the two groups. For entities, it’s the components themselves that are updated directly, reflecting those results by altering their state and the state of the enclosing entity. Modules rely on events to receive data detailing a particular, well, event of interest. Not only that, but the type of change done in an update is also different between entities and modules. Entities change the state of the game simulation - what the viewer interacts with, and modules change their internal systems as events are received - systems that are effectively tools for a module’s components to use during their updates. Module updates occur at the start of each input and render phase pass, which is done to optimize performance. Component updates happen in each phase, and it is up to the developer to choose which phase all components contained in a state update in when the state is created. For this reason, entities will most likely have updates that span all three phases.

A diagram showing what this all looks like can be seen below.

Events vs. Commands

The beauty of separating parts of our engine into modules and then decoupling the communication between them is that it allows us to work on any system in the engine without an explicit understanding of what’s going on behind the scenes everywhere else. What I mean by this is that if I’m writing code for the physics module, I don’t have to know how the graphics module works in order for the two modules to integrate. All I have to do is just notify the graphics module of notable events, and it decides how to respond to that. I think it’s important to recognize the difference between events and commands and role the former plays in decoupling our modules. When using commands, we are decoupling a direct method call between classes, but we still command another class by calling its methods and therefore must have knowledge of its existence and function. With events however, we broadcast an event which has already happened, and it’s up to other systems to respond to that. Therefore, the system broadcasting an event doesn’t need to know about other systems in order for things to happen in response to the event, which is just what we need for our modules. A command/message/job represents something that needs to be done, while an event represents something that has happened. Within the engine, events are reserved for inter-module communication, as this needs to be heavily decoupled. For more tightly related classes and systems, commands will typically be used, which themselves sometimes vary in form. For example, the Command class is widely used across the engine, while Runnables, which are another form of the command pattern, are used extensively in the Core module.

Multithreading

The engine core incorporates a hybrid approach to multithreading, using both task-parallel and data-parallel threading. In order to be suitable for the engine, the threading solution had to hit three goals.

-

Must remain deterministic

-

Must scale with more cores

-

Must avoid excessive blocking and waiting

To achieve these, different threading implementations were used for entities and modules.

Data-Parallel - Entity Updates

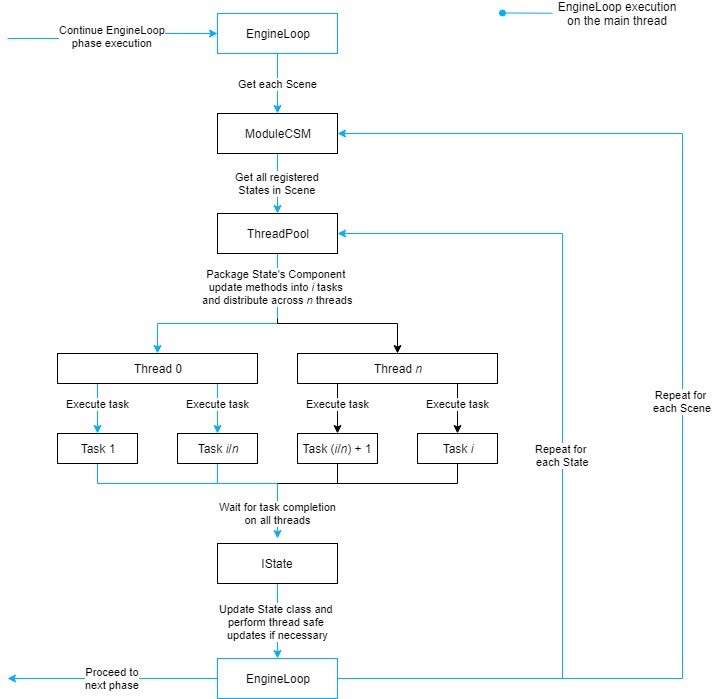

If we were to use the task-parallel threading approach for entity updates, we might create a task for each state in a phase and then run those tasks concurrently. However, when it comes to dealing with entities, this method of multithreading is too agranular, introducing either excessive locking and synchronization or non-deterministic behaviour into the engine loop. Instead, what we’ll do is much more akin to the style of threading performed by SIMD parallel processors. Because there may be multiple different entity components (each from a different state) that are updated within one of the engine loop phases, and which may modify the same variables in their enclosing entity, if each component is updated in parallel then potential race conditions arise. To solve this issue, we can multithread the component updates within a single state while preserving the sequence of component updates from different states. This is done by packaging batches of component updates into a runnable, then distributing the runnables amongst all available threads. Components can read (but not write) data from the enclosing state and other components during an update. When finished their update tasks, components can acquire the location of their back-buffer from the state class and write any updated data to that. Once all the component updates have been completed, the main thread performs any necessary updates to the state class itself, and then the process repeats for the remaining states in the engine loop phase. The below diagram shows what this looks like.

The order of component updates remains sequential, thus preventing entity state overwrites between components within the same entity. And because components don’t manipulate the state of components from other entities, determinism is maintained.

Task-Parallel - Event Queue

Instead of treating every single class as a subject, because the observer pattern is to be used between entire systems, we will instead treat each module as a subject. This offers a nice balance between maintaining the granularity of each subject and its events, and having structured control over subject-observer groups and dispatching notifications.

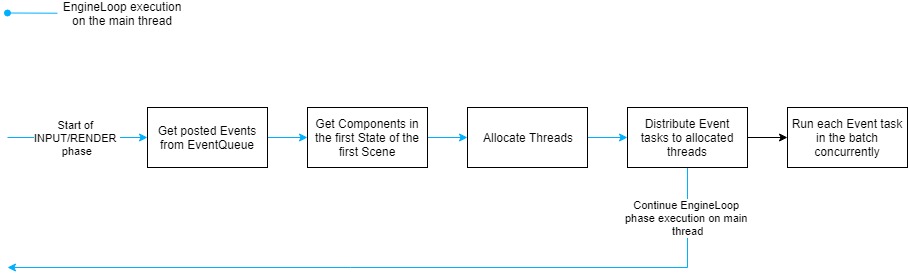

We can then transfer observer registration from the subject of interest to an external queueing system, which holds references to all subjects and observers. This allows us to apply our observer pattern across multiple threads, since we can control access to and synchronization of this central queue (which itself holds a thread pool - something that isn’t possible without introducing a slew of new dependencies when this responsibility is left up to individual subjects to implement). And a queue is required so that when all the worker threads are busy, there is somewhere to store the events without blocking the engine loop while waiting for the threads to finish up. However, you might be wondering when modules receive these events, and how it fits in with the rest of the engine loop. Well, because all threads must be utilized during state updates, module notifications must occur in between these updates. More specifically, they will start at the beginning of both the input and render phases. Why these two and not the update phase? Well, I figure that the majority of component update processing will happen in the update stage, so it, out of the three phases, will yield the greatest performance benefit from having access to all threads. The input and render phases are also called at a higher frequency, which means that modules will receive events quicker. This is where task-parallel threading comes into play, as at the start of each phase, each event (or groups of events) are dispatched from a central queue to be handled by interested modules on another thread. The ModuleCSM then has the remaining number of threads to run component updates on concurrently, which starts immediately after the event handling has been kicked off. In order to determine how many threads should be allocated for component updates and for event handling the ratio of components to queued events is used. The resulting EventQueue threading solution looks like so: